The Rolfing® Technique of Connective Tissue Manipulation

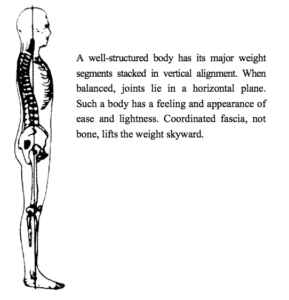

Structural Integration (SI) is a technique for reordering the body to bring its major segments — head, shoulders, thorax, pelvis and legs — toward a vertical alignment. Generally speaking, the Rolfing process lengthens the body, approaching an ideal in which the left and right sides of the body arc more nearly balanced and in which the pelvis approaches horizontal, permitting the weight of the trunk to fall directly over the pelvis; the head rides above the spine, the spine curves are shallow, and the legs connect vertically to support the bottom of the pelvis.

MAN DEALS WITH GRAVITY in a way different from other animals. Rather than planting himself firmly on four or more supports, he has swung himself up on a narrow, unstable two-point base; he is less secure but more dynamic, more flexible, with two of his limbs free for an active and mobile contact with his world. The tightrope walker presents this image of balance and lightness in ourselves, a delicate adaptability to the forces acting on us. Man’s center of gravity is high, giving him a state of high potential energy.

The key to this efficient and graceful relationship to the field of gravity is a body in which the weight transmission remains close to a vertical central axis. The amount of energy required to move weight around a vertical axis (the moment of inertia) decreases geometrically as the weight is moved toward the axis, as skaters and ballet dancers know when they achieve fast spins by pulling in their arms and legs and lengthening their bodies.

If we picture the body as a stack of partially independent weight segments, the least energy will be expended in rotational movement when the blocks are stacked directly above one another. This stacking will also result in the highest possible center of gravity since the spinal curves will be shallow and the body consequently longer.

THE AVERAGE INDIVIDUAL has let his body weight slip out from the vertical axis, that is, he has shortened his body. His head has slumped forward and his buttocks are probably carried up and back. Most likely his body has twisted as it has slumped; one shoulder or one hip may lead the other as he walks. Knees may track out or in and misaligned ankles may throw his weight to the outside of his feet. One foot probably carries more weight than the other.

How do bodies become unbalanced? From a purely mechanical perspective, distortions are the result of the remarkable plasticity of the body; the tendency of fascia, the connective tissue which envelops the muscles and which gives the body shape, to be remolded by applied force. The primary force comes from repeated patterns of self-use, the way an individual walks, sits or sleeps. These patterns, which are generally established in infancy, draw heavily on parental example and on the other environmental factors like diapers, shoes and school desks. Inefficient patterns of behavior set themselves in the fascial network as unbalanced patterns of structure.

Distortions also enter our plastic bodies through accidents: a fall from a bicycle, for example, that twists a knee, causing a limp for a few weeks. The shifting of weight to the strong leg restructures the play of muscular effort not only in the legs, but through the pelvis, up the spine, eventually throughout the whole body. Although the limp seems to disappear as the knee strengthens, the system of compensations leaves its imprint in a broad, complex pattern of shortened fascia.

Patterns of imbalance tend to reinforce themselves; they feel comfortable and natural — balanced, in fact. Over the years they deepen by repetition, and the weight centers more progressively further from the vertical axis. Gravity becomes an increasingly destructive force.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF IMBALANCE are surprisingly broad. When the body’s blocks, shifted in various directions out from the vertical axis, are no longer stacked on top of one another, both skeleton and musculature are forced into an inefficient weight-bearing function. For example, the head of the lady pictured in this article is no longer being: carried skyward by the cervical spine: instead; the muscles of the neck and upper back, designed as dynamic guide wires to move and balance the head, are forced into chronic tension required to support its weight.

The function of most muscles is to contract in order to bring about movement, to release in order to bring about movement, and then to release again in order to be prepared for new movement. When they consistently take on the weight-bearing function of bone, their fascial envelopes tend to take on the hard and inelastic quality of bone. Tightness spreads through the fascial network: the body- locks up and the joints lose their freedom.

Joints lose their ease of movement not only from the tightening of fascial planes which cross them, but also from the fact that as the two body parts that relate to one another through the joint lose the integrity,’ of their relationship_ the articulating surfaces of the joint itself do not meet in a way appropriate to their structure. If the bones of the lower leg, for example, are twisted outward and the bone of the thigh inward, a common situation_ the knee is likely to be a troublesome or unstable one. The movement of the leg – indeed of the whole body – will lack the grace which comes of movement that is appropriate to the structure. We are likely to call such movement “disjointed.- a sign of our intuitive understanding that it is not integrated.

Circulation is restricted as the body tightens because the vessels run in and through the fascial network. The depression of the upper chest, a consequence in part of the shifting forward of the head, limits abdominal and pelvic cavities, often impairing function. Swayback, for example, spills the abdominal viscera forward into a protruding abdomen, changing the spatial relationships between organs and the direction of pressures on them.

Bodies may also show imbalance of tonus between the voluntary musculature of the surface and the deeper, smaller, slower moving and more reflexive muscles such as those which lie around the spinal column, Inability to lengthen the spine because of tightened fascia will tend to throw the deeper muscles out of use, resulting in a jerky movement style which is neurologically imbalanced toward cerebral or voluntary control at the expense of the reflexive centers of the spinal cord.

The state of balance or imbalance in our bodies – their relationship to the field of gravity – is reflected in feeling states, since emotion is intimately involved with muscular tonus. Balance might be thought of in a healthy organism as a resting state, a capacity and a preparedness for responses of all kinds depending on the nature of the stimulus. Imbalance,

then, is the response itself – the movement, or impulse to movement, which completes itself by a return to balance when the response has spent itself. But our lives are such that many responses never do complete themselves. A child with a threatening mother, for example, may continually be shrinking away, lowering his head, raising his shoulders and depressing his chest until the pattern becomes a norm for him: or he may, like a racer waiting for a starting signal that never comes, build tension in his legs through an unfulfilled impulse to run away. The muscular tension and the emotion are two aspects of the same organic pattern.

Chronic muscular tension is a permanent shortening of fascial structures; to the extent to which they arc no longer capable of lengthening, they have built into the person not only a way of moving but a way of feeling, so that one particular kind of emotion characterizes his response to a wide range of stimuli. His response, then, is always in part to his past-to those strong influences in reaction to which his structural imbalances were developed. This programming marks a loss in his ability to respond with full appropriateness to present situations.

One individual may perceive his losing fight with gravity as a sharp pain in his back, another as the unflattering contour of his body, another as constant fatigue, yet another as an unrelentingly threatening environment. Those over 40 may begin to call it old age. And yet all these signals may be pointing to a single problem, so ubiquitous in their own structure as \ yell as in function that it has been ignored: they are off balance. They are all at war with gravity.

ROLFING SI REBALANCES the fascial network by taking advantage of its tendency to hold the shapes induced by applied force. In a carefully worked-out sequence of manipulations, the Rolfer reverses the randomizing influence of the environment, moving tissue back toward the symmetry and balance that the architecture of the body so clearly calls for.

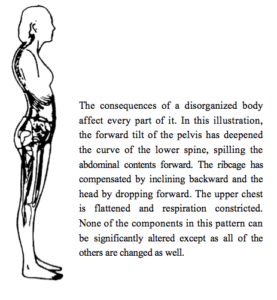

The consequences of a disorganized body affect every part of it. In this illustration, the forward tilt of the pelvis has deepened the curve of the lower spine, spilling the abdominal contents forward. The ribcage has compensated by inclining backward and the head by dropping forward. The upper chest is flattened and respiration constricted. None of the components in this pattern can be significantly altered except as all of the others are changed as well.

The consequences of a disorganized body affect every part of it. In this illustration, the forward tilt of the pelvis has deepened the curve of the lower spine, spilling the abdominal contents forward. The ribcage has compensated by inclining backward and the head by dropping forward. The upper chest is flattened and respiration constricted. None of the components in this pattern can be significantly altered except as all of the others are changed as well.

Consistent misplacement of weight anywhere in the body evokes a compensatory pattern of tightening throughout the fascial system. For example, the forward slump of the head of the lady in the illustration is directly related to the tilting of her pelvis and to the locking of her knees, to select only three parts from the pattern. Relief given by freeing either neck or knees alone would be temporary because other parts of the pattern would later force the relived part to function in harmony with them. For that reason the Rolling practitioner looks at the entire fascial structure and works to rebalance it.

Rolfing SI takes place in a series of ten sessions lasting about an hour each and usually spaced a week or more apart. It proceeds from the surface of the body toward deeper levels and from the relief of specific local areas of contraction and displacement in the first seven hours to the reorganization of the relationships between major segments of the body in the last three.

The Rolfer must apply sufficient force to stretch and move tissue, furthermore, he or she is frequently working in tissue whose chronic tension carries an emotional load. There may be some discomfort that disappears immediately when the pressure is removed. And there is sometime soreness, of the kind felt when muscles are overworked, that lasts a few days. Pain frequently marks an emotional release, and mad be strongly colored by associated emotions. People who are receiving Rolling SI often recall specific traumatic episodes associated with particular parts of the body: with or without such recall, the release of chronic contractions has an emotionally purgative effect. “I feel as though I have unloaded years of accumulated grief,” was the comment of one person who cried as tension was released from his ribcage.

THE RESULTS OF ROLFING SI are as varied and complex as the organisms being altered. Generally speaking, the body acquires a lift, or lightness as the head and chest go up and the trunk lengthens: the pelvis, in horizontalizing. brings the abdomen and buttocks in; the knees and feet track more nearly forward and the soles of the feet meet the ground more squarely. As the joints gain freedom the major segments of the body rotate and hinge more freely on one another. There is less pitching of the body from side to side in walking and less raising of the body weight with each step. Conserved energy is available for other purposes.

The lengthening and centering of the body along its vertical axis together with an increased engagement of the deep musculature brings a quieting, a flexible sense of self-possession that tends to replace earlier pre-structured responses. Since this new sense of self is presented to others in the carriage of the body, even casual social contacts may seem altered: increased self- trust communicates itself as trust-worthiness.

The long-range consequences of Rolfing SI vary a great deal, since the body continues to be plastic and therefore subject to forces around and within, both constructive and destructive. Most people undergo a spontaneous integration process for

at least a year after their Rolfing sessions as their improved balance manifests itself throughout the body. Especially if a conscious effort is made to replace old destructive habits of self-use, structural changes tend to bring about behavioral changes as people use new, more balanced patterns of movement and meet situations with less tension. Many people have experienced a striking reversal when a vicious cycle of energy drain and structural break down has been replaced by progressive self-enhancement. After a period of months or years some people may wish to return for further sessions, including the advanced series.

RESEARCH on Rolfing SI has provided objective quantitative data about its effects. As early as the 1970s, Dr. Valerie Hunt, Director of the Movement Behavior Laboratory at UCLA and Dr. Julian Silverman, Research Specialist of the California Department of Mental Hygiene, conducted experiments at Agnew’s State Hospital in which subjects were tested before and after Rolfing Si sessions for changes in neurological control of the muscles, for variation in responses to stimuli, and for biochemical changes. Their findings indicated that after Rolfing work, there was a more efficient use of the muscles, conserved energy, increased refinement of response and a tendency for motor control to shift toward the more reflexive spinal centers.

RESEARCH on Rolfing SI has provided objective quantitative data about its effects. As early as the 1970s, Dr. Valerie Hunt, Director of the Movement Behavior Laboratory at UCLA and Dr. Julian Silverman, Research Specialist of the California Department of Mental Hygiene, conducted experiments at Agnew’s State Hospital in which subjects were tested before and after Rolfing Si sessions for changes in neurological control of the muscles, for variation in responses to stimuli, and for biochemical changes. Their findings indicated that after Rolfing work, there was a more efficient use of the muscles, conserved energy, increased refinement of response and a tendency for motor control to shift toward the more reflexive spinal centers.

Over the decades, research has continued, looking at the effects of Rolling SI on cerebral palsy in both adults and children, the treatment of chronic pain, the treatment of cervical spine dysfunction, improvement in balance, the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. as well as effects on anxiety and other psychological reactions.

Other research is planned or in progress; please visit www.rolf.org/research for current information.

DR. IDA P. ROLF (1896-1979), originally an organic chemist with the Rockefeller Institute, perfected the process of Rolfing Structural Integration over many years before establishing a systematic training program and a professional organization. Nearly 1900 Certified RolfersTM and Rolf Movement® practitioners are located throughout the world. Training programs are currently conducted in the United States, Europe, and Brazil with regional offices also in Australia, Canada and Japan.

To find Certified Rolfers and Rolf Moment practitioners in your local area, please visit the website at: http://find.rolf.org

Feel free to contact us with any questions at:

The Rolf Institute® of Structural Integration

(303) 449-5903 / (800) 530-8875 Fax (303) 449-5978 [email protected]

Rev. 10/2012

© Copyright 1976, 2003, 2012 by The Rolf Institute®. All rights reserved. “RolferTM,” Rolfing®,” “Rolf Movement®,” “The Rolf Institute®,” and Little Boy Logo are all servicemarks of The Rolf Institute. They can only be used by licensed members in good standing of The Rolf Institute.